Computer games have come a long way over the past few decades, to put it very mildly. Multiplayer gaming has become a focal point of the entire industry, at least in terms of big-budget PC games and console systems. There have also been huge advancements in games that make use of Adobe Flash Player and JavaScript to provide fun, addicting games that you can play right in your browser. Browser-based gaming has come a long way, to the point where we can even play games like Quake 3 directly in the browser using technology that compiles the code fast enough to play.

Nowadays it’s hard to imagine a game that doesn’t implement some sort of web-based functionality, whether you’re posting your high scores for Candy Crush, or you’re playing a Battlefield 4 conquest mission in a 64-player free-for-all. Much of the time this functionality takes on the form of multiplayer gameplay, i.e. competing with other players remotely via a designated server for the game.

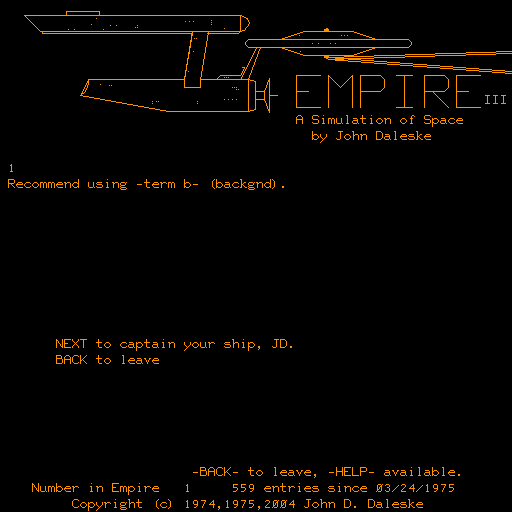

So when did game designers first try to make games that were playable on a network? Well, the first several examples of actual multiplayer games actually pre-dated the Internet. It all began with a game called ‘Empire’, which was created in 1973 by a guy named John Daleske while he was a student at Iowa State University.

Anyway, Empire allowed players to compete against one another in a space combat simulator over a network called PLATO. PLATO stands for Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations. It came about in around 1960 at the University of Illinois, as a system of graphics terminals (think early desktop PCs) supported by about a dozen networked mainframe computers. PLATO has a fascinating history that I don’t want to delve into too deeply right now, but the development of the system formed the basis for some of our most beloved internet features. By 1976, PLATO had support for primitive versions of e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging, remote screen sharing, and even emoticons. It also provided the basis for multiplayer gaming, starting with Empire, but expanding to many other types of games throughout the 70s and 80s. Empire went through several different iterations, and by the time Empire IV came out in 1977, they had even given players the ability to live chat with one another. Just to give you some idea of the gameplay, players did not have a mouse, and had to enter all commands via typing. The commands involved punching in coordinates for course changes, and firing weapons based on user-entered degree headings. The object of the game was to conquer the galaxy, naturally, and up to 30 players could be in the game at once, engaging in dogfights against one another to try and gain a foothold in the galactic battle.

Now, skipping ahead to the 1990s, you had some major players come on the scene in terms of multiplayer gaming. Arguably the biggest title out of all of these was Doom, which if you’re not familiar is a sci-fi / horror themed first-person shooter that came out in 1993. Some say it is the greatest PC game of all time, but that’s a matter of opinion. Doom was created by my favorite programmer John Carmack (he also was behind Commander Keen, Wolfenstein 3D, and Quake), and the game was immediately notable for its markedly improved 3D graphics and exciting, imaginative gameplay and storyline. Anyway, as it relates to multiplayer gaming, Doom had a competitive online mode that ran over something called the DWANGO network, which was an online gaming platform launched in 1994. It became known right off the bat for its compatibility with Doom, and it served as a service to match up players looking to compete. Since this was before the actual Internet, the way it worked was players would pay a fee and run the DWANGO client software to connect to a DWANGO server by dialing a phone number in Houston, Texas. DWANGO is actually a thriving telecom company in Japan to this day. Despite the (to our standards) primitive interface, DWANGO actually allowed players to chat in a lobby, organize games, and connect to play Doom together, among many other games that soon came to be supported as well.

So aside from Empire and Doom, what represented the next major leap forward in online gaming? Some say Quake, which was another first-person shooter that made online play an integral part of the product, rather than treating it as an add-on as with Doom, but let’s talk about the year 2000 for a second. I would argue that the year 2000 ushered in the real modern epoch of online gaming, with two of the most popular PC titles ever made, ones that rival Doom in terms of legendary reputation amongst gamers. I’m talking of course about Diablo 2 and Counter-Strike. Counter-Strike was actually a third-party mod of the game Half-Life. Even though the only way to play the game was online, it sold well over 4 million copies, along with countless copies that came free with the purchase of Half-Life. As for Diablo 2, it actually claimed a Guiness World Record for the fast selling computer game of all time, selling over a million copies in 2 weeks. Besides the speed at which it flew off the shelves, Diablo 2 was notable because it allowed a player to use their local player in online matches. Based on these two games, it was clear that competitive online multiplayer was here to stay.

So what else happened? Well, big budget titles have continued to come out of course, and as I said at the beginning, it’s hard to imagine any current game or system that does not rely on the internet in some way as part of its core user experience. I sort of ran out of time to talk too much about browser-based gaming, but I thought Steven’s example of playing Quake directly in the browser was very interesting, so I wanted to take a slightly closer look at that. If you go to quakejs.com, you’ll find one brilliant programmer’s project to port Quake 3 directly into JavaScript, using something called ioquake3, which is the engine that allows the programmer to work with, modify, and run the source code of that particular game.

So, the game itself was written in C, which is interesting for a few reasons. C++ would have been the other, possibly more logical choice, but it only came out about a year before Quake 3 came out, so the developers had pretty much already done about half the work on the game before that actually came out. Speaking of the dev team, John Carmack led the way again, and he has stated that Quake 3 was his favorite game he ever worked on.

At any rate, QuakeJS uses a compiler called Emscripten to take that C source code from the game, and compile it directly to JavaScript, which then of course lets you run the game in our fancy modern browsers. Pretty cool right? Since Quake 3 contains several dynamic libraries such as OpenGL for its graphics, Emscripten also contains versions of these libraries translated into pure JavaScript. Emscripten then links these in and relies upon current, powerful HTML5 technology to find the right counterpart. The fact that this one guy (his name is Anthony Pesch) figured out a way to completely port a game like Quake 3 into a browser using JavaScript is pretty impressive, and his write-up of how he did it goes way beyond my actual ability to discuss, but I encourage you to try out the game and check out his blog post to get a sense of how compilers work with JavaScript.

Resources:

“A Massive History of Multiplayer Online Gaming

ioquake3 Engine

Emscripten Site

Anthony Pesch’s Blog Post on porting Quake 3

QuakeJS